Maïs

Maize

Zea mays

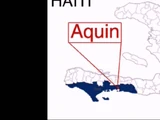

In acreage, maize shares the honors with sorghum as one of Haiti's two leading crops. Throughout the country it occupies a sizeable percentage of the cultivated land from about five percent in the sodden uplands north of Camp-Perrin to 75 percent on the plateau of Seguin. Areas that regularly produce a surplus of maize for sale in the city markets are the Grande-Anse, the plateau of Seguin, and the hinterland of Saltrou. Sorghum is more abundant than maize in very dry districts such as Aquin and on steep stony slopes in moderately dry districts such as the coast between Port-au-Prince and the Léogâne Plain. However, in the very humid Grande-Anse and at altitudes above 500 meters (1,640 feet), there is little sorghum, but maize is a major crop. Sugar cane and tree crops are given priority on deep level soils in the Grande-Anse so that maize is relegated to the thin soils on the slopes.

Where two crops of maize are raised they are sown at the beginning of the spring rainy season (usually in March) and during the autumn rainy season (August or later). Customarily, the larger acreage is planted in the spring. At high altitudes, as at Furcy, Seguin, Savane Zombi, only one crop is planted in the spring. On the Cayes Plain, most of the maize is seeded in the spring to be supplanted by sorghum in the fall. Sometimes the best ears are selected and saved for seed, but very often the seed corn is purchased because of the difficulty of storing grain safe from the ravages of weevils. Four or five kernels are dropped in each hole made with a machete, hoe or dibble with spacing of three to four feet between holes. In the Grande-Anse, at Chambellan, a woman digs the holes with a machete and plants the seed by herself, while on the Cayes Plain, at Chantal, a boy makes the holes with a hoe and a girl drops the seed in and covers it. Popular belief is that if she covers the corn with her heel the ears of corn will be red, with the ball of her foot, they will be white. The corn is cultivated but once in most areas, two times at high altitudes where it takes as long as nine months to mature. Only in the region of Cayes was observed the practice of hilling, which is done simultaneously with cultivation.

Most of the corn raised in Haiti is of the old West Indian flint stock in contrast with the Dominican Republic, where recently introduced varieties of dent corn are common. Haitian agronomists give resistance to weevils and smut as the reasons for retention of the flint. The natives distinguish varieties of flint corn on the basis of color and length of growing season. Yellow, red and white varieties, in order of decreasing abundance, of both long and short season corn are raised. Appropriately, the red corn is called maïs du vin, for its kernels have the hue or red wine. Red cobs, tassels, silk, stalks and husks are associated with the red flint, and often with the yellow flint as well.

In dry regions, as at Saltrou, two crops of three-month corn are grown in a year; in the moist lands below 1,000 meters (3,280 feet), one or two crops of five-month corn are grown; and in the cool highlands one crop of long season corn is raised. The three-month corn is preferred at Saltrou because of the short rainy seasons, whereas in areas of more abundant, dependable, and better distributed rainfall, long season corn is preferred for its heavier yields and the fact that the ears are high enough on the stalks so that dogs cannot reach them. Half-starved, the numerous farm dogs eat corn in the milk. Because of low temperatures, five-month corn takes eight to nine months to mature at Furcy and Seguin.

Birds, rats, mice and earworms eat the corn in the field. Of the former, parrots (Amazona ventralis), woodpeckers (Centurus stiatus) and crows (Corvus palmarum) are among the most bothersome. Also, smut and leaf rust afflict the growing corn.

Harvesting the corn is primarily a woman's job. The corn on the cob is stored in small attics in the gables or above the porches of the farm buildings, or - strung on a rope to form a cylinder of radially arranged cobs - it is suspended from a pole supported between two posts, from a tree or from a horizontal stick thrust through a hole in the trunk of a royal palm. The royal palm is favored for this purpose because rats cannot climb its smooth trunk. For rat protection the trees and posts are girdled with thorns, sheet metal, or protruding rings of clay. When the corn is stored thus exposed to the elements it is left unhusked. A better arrangement, which is often employed, is a large, keg-shaped, covered basket woven of liana with wide interstices that permit good ventilation. In such a basket, propped in the crotch of a tree, the corn is safe from both birds and rats. In six months, weevils eat 30 to 40 percent of the maize stored on poles or trees. The maize it treated for weevils with smoke from a fire smothered in green leaves.

Immature maize is eaten boiled or roasted on the cob, or it may be grated, mixed with spices and syrup, wrapped in a piece of banana leaf, and boiled. This food dish which resembles a tamale, and is called doucounou, may also be made from ground dry corn; and salt, meat and chili may take the place of the spices and syrup. A popular beverage, akassa, often written AK100, is prepared by boiling corn, mashing it in a mortar, mixing the mash with water, skimming off the hulls, allowing the mixture to stand overnight, decanting the water and adding milk and sugar to the residuum of corn starch. Another mode of preparation of akassa is to soak the corn overnight, grind it in a mortar, squeeze the mash through a cloth, to mix after with the mash that does not pass through the cloth and to regrind it and squeeze it again, and finally, to cook all the material that has been forced through the cloth. Milk and sugar may be added at the discretion of the cook. Whole kernels of shelled corn are soaked and boiled with chili pepper and a bit of meat. To make corn meal, the shelled corn is pounded in a mortar to knock off the hulls, which are separated by winnowing before the corn is returned to the mortar to be ground fine. From the corn meal, unleavened bread is made, often with the addition of wheat flour, chopped coconut and syrup. Mush (moussa) is made by boiling the corn meal with beans, salt, fat, meat and chili pepper.

All items (45)